The DFDL language has a composition property known as referential transparency. It is not supposed to matter whether you lift a part of the schema out and create a reusable group, reusable type, or reusable element from it.

Because DFDL (version 1.0) does not allow recursive definitions of any kind, it is theoretically possible to implement this by treating all reusable definitions in the language like macros. I.e., inline-expand all definitions at their point of use. This will work for schemas up to some size. However, it leads to an unacceptable expansion in schema compilation time and space, as the size of the schema once all these inline substitutions have been performed can be exponentially larger than the original non-substituted schema.

To avoid this undesirable combinatorial explosion, the Daffodil schema compiler arranges to achieve the same macro-like semantics, while still sharing the core parts of the reusable components so they need only be compiled once for each unique way the component is used.

This is also part of eventually enabling an extension of the DFDL language to allow recursive definitions.

The dfdl:alignment property is one of the largest contributors to complexity in sharing objects by the schema compiler.

Alignment will be used as the example in this design note to illustrate the schema compiler behavior.

DSOM is the Daffodil Schema Object Model. Within this model, the components from a DFDL schema that actually have representations in the data stream or are computed, are called terms and DSOM models them as subclasses of the class/trait Term. Terms which are computed (via dfdl:inputValueCalc) are said to have no representation in the data stream.

For this discussion we are concerned only with concrete terms, meaning those that do have representation.

The classes in Daffodil that are used for concrete terms are:

ElementRef

Root (A degenerate element ref to the root element)

LocalElementDecl

the quasi-elements:

PrefixLengthQuasiElementDecl (Fake local element decl used for the length fields of Prefixed-length types)

RepTypeQuasiElementDecl (Fake local element decl used as the representation of elements that are computed via the dfdl:repType mechanism.)

Sequence

SequenceGroupRef

ChoiceBranchImpliedSequence (The sequence that is inserted when a choice branch is a single element decl/ref)

Choice

ChoiceGroupRef

A UML Diagram is available showing these classes.

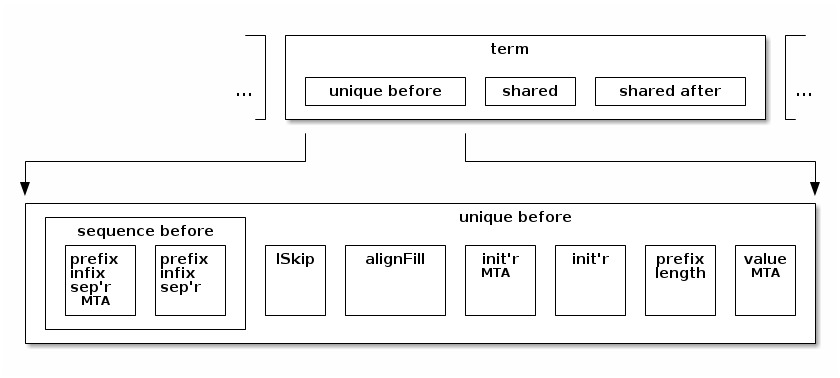

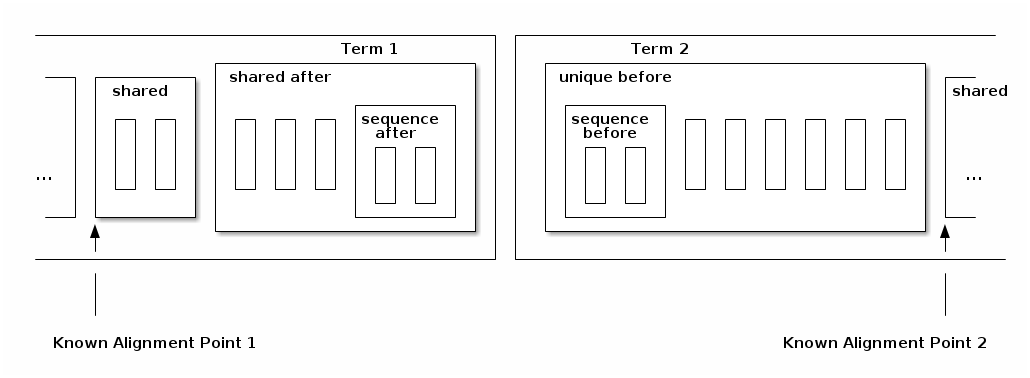

Consider the representation of a term, which we call the term’s region, as appearing between two other term regions in the data stream as illustrated below:

In the above, lower position bits are to the left. Higher position bits to the right. In the diagram, we see that the term’s region consists of 3 sub-regions, named unique before, shared, and shared after. Each term appears in a context of possible additional terms before it and after it which are shown with ellipsis above.

A term can be an element or a model-group (sequence or choice). By far the most common situation is that a term appears inside a model group. There are two exceptions. The root, and the model-group of a complex type.

The core idea here is that we are separating the representation of a term into unique and shared parts. The unique region is affected by the surrounding model group context. The shared regions are, in many cases, sharable across instances of this term and is independent of the surrounding model-group context. So if the term was defined by way of a reusable global definition, then the goal is that there need be only one implementation of the shared part(s).

There are some limits to this sharing. A single implementation is not always achievable, but generally one or a small number of implementations are possible.

Consider if this term above was defined by way of a XSD group reference. The DFDL properties expressed on the group reference must be combined with those expressed on the group definition, to form the complete set of properties associated with the term. This combining creates situations where a given shared group definition can have wildly different representations for different uses. Consider this:

<group name="g">

<sequence>

<element name="a" type="xs:int"/>

<element name="b" type="xs:int"/>

<element name="c" type="xs:int"/>

</sequence>

</group>

....

<element name="e">

<complexType>

<sequence>

... some stuff here ...

<group ref="tns:g" dfdl:separator="|"/> <!-- separated -->

... more stuff here ...

<group ref="tns:g"/> <!-- not separated -->

... yet more stuff here ...

</sequence>

</complexType>

</element>The two uses of the group definition for 'g' are wildly different, in that one has separators, the other does not.

This is a rather extreme example, but DFDL implementations must allow for this.

Experience with DFDL schemas to-date (2020-01-21) is that this is very rare and appears only in test cases designed to exercise it. However, less extreme versions of this are possible, such as different uses all being separated and delimited textual data, but where the distinct uses do not all use the same separator characters, so the separator to be used would be specified differently on each group reference. Another expected variation could be separated sequence groups where some uses are infix separator and others are prefix or postfix separator.

Anecdotally, the vast majority of schemas seen to-date reuse groups entirely, that is specifying no properties at all on the group reference.

We define the property environment or PropEnv of a term, as the complete set of properties for that term, combining them from all the schema components that define the term. This can include element references, group references, local or global element declarations, global group definitions, and local and global type definitions.

A key observation is that the PropEnv of a term is entirely defined by:

local properties (including any dfdl:ref property) on the schema component for the term.

E.g., for an element reference, the local properties expressed on the element reference itself.

default format object at top level of the schema where the term lexically appears.

definition object being referenced.

E.g., for an element reference, the global element declaration being referenced.

So if two terms, say group references, have the same PropEnv, then we can share much about their definitions when implementing them.

Hence, when constructing the Daffodil schema compiler’s representation for a term, we can maintain a cache for each global definition, with the key of the cache being the PropEnv. When a given term uses a global definition, if the point of use has the same PropEnv as another, both can share the part of the term that is context independent, that is, the shared region.

The actual components of the PropEnv of a term are slighly more complicated than described above. The table below gives the components of the PropEnv for the various kinds of terms. Note that the "local properties" below includes any dfdl:ref property if it appears, but equality of any property which has as its value a QName, like dfdl:ref, the property value is based on a resolved QName, not the QName string.

| Term Definition (one PropEnv subtype per) | PropEnv Components |

|---|---|

Local Element Decl with type reference |

|

Local Element Decl with anonymous Simple Type Definition |

|

Local Element Decl with anonymous complex type definition |

|

Element Reference to Global Element Decl |

|

Lookups by PropEnv compare sets by equality of members, and object references by pointer equality i.e, eq comparison.

This definition of PropEnv can be improved by memoizing the construction of default format objects, so that equivalent default formats from different schema documents are represented by the same object. That is, so that multiple schema documents each containing:

<dfdl:format ref="prefix:formatName"/>are instantiated as the same object when the QName resolves to the same format object.

The division of the reprsentation into the unique part which appears before the shared parts indicates where we can share implementation, and where we must have unique context-specific implementation for the term.

To understand this better, the below breaks down the sub-regions of a term further. First we look at the details of the unique-before region:

The sub-regions within the unique before region are:

prefix infix sep’r MTA - mandatory text alignment for a separator in infix or prefix position. When a separator is defined, this region is populated with up to 7 bits to obtain text alignment for the characters of the separator in the specified charset encoding. Note that this encoding and that of the term’s initator/terminator are not necessarily the same encoding.

prefix infix sep’r - separator when defined and in prefix or infix position. This consists of text characters.

lSkip - leading skip region. This is fixed length (commonly 0)

alignFill - alignment fill region. This dynamically sized region depends on the bit position where it starts.

init’r MTA - mandatory text alignment for initiator. When an initiator is defined, this region is populated with up to 7 bits to obtain text alignment for the characters of the initiator in specified charset encoding.

init’r - initiator. This consists of text characters.

prefix length - (element terms only) the prefix length. Sub-detail of this region is not shown here. The PrefixLengthQuasiElementDecl class is used to represent this subregion in DSOM.

value MTA - (element terms only, simple type only) mandatory text alignment for the value. When the value has text representation this insures those characters start on the right bit-boundary for characters of the specified charset encoding.

The sizes of the alignment regions (alignFill, and the MTA regions) in the above all depend on where the start of this term is. That depends on where the prior term ends, if there is a prior term. That is, the sizes of the alignment regions depend on the enclosing model groups, and what can appear before this term in that nest.

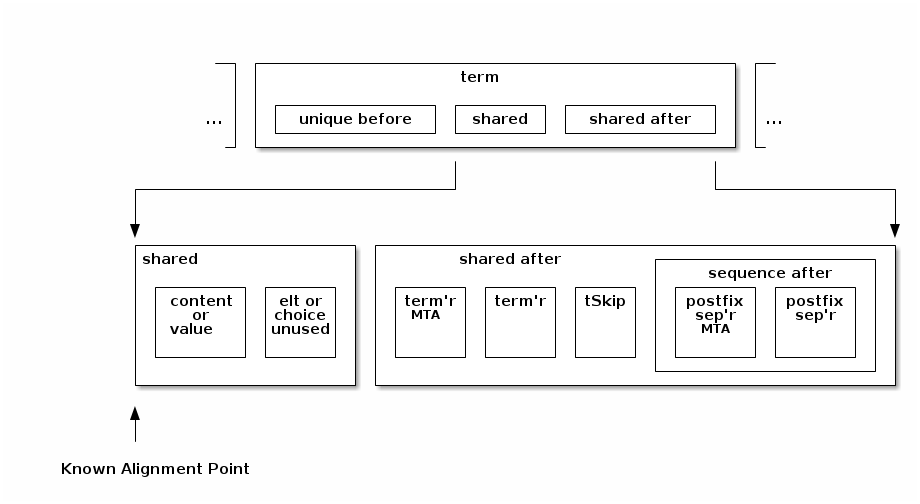

Now we look at an expansion of the shared regions:

It is key that the shared region can assume the alignment fill and MTA regions have been sized per the requirements of this term. Hence, the shared region is context independent and its implementation - in schema compiler objects and in runtime structure representation, need only be represented once.

|

|

Corner Case: Interior Alignment

The semantics here aren’t identical to those of macro expansion, but the difference is hard to detect. The DFDL Spec (recent draft) includes a section (23.6 in the linked draft) on this interior alignment problem. The technique for approximating alignment info described here is slighly less precise in its analysis because it resets its knowledge of the alignment at each known alignment point. Whereas pure macro expansion could carry forward knowledge of alignment and perhaps optimize out more alignment fill regions. Hence, it’s possible that the technique here will leave some alignment fill regions in place and thereby some formats will experience circular deadlocks when unparsing due to this variable-length interior-alignment. The Daffodil test suite includes examples of this interior alignment that cause unparser circular deadlocks. (see testOutputValueCalcVariableLengthThenAlignmentDeadlock) |

The shared region contains a text or simple binary value, a nil representation, or inductively, a sequence of terms. When the term is an element of complex type, an element unused region can follow (depending on the length kind), and if the term is a choice with dfdl:choiceLengthKind='explicit' then a choice unused region can follow.

Then, after the shared part, the shared-after region has these subregions:

term’r MTA - mandatory text alignment for the terminator.

term’r - terminator

tSkip - trailing skip region. This is fixed length (commonly 0)

postfix sep’r MTA - - mandatory text alignment for a separator in postfix position. When a separator is defined, this region is populated with up to 7 bits to obtain text alignment for the characters of the separator in the specified charset encoding. Note that this encoding and that of the term’s initator/terminator are not necessarily the same encoding.

postfix sep’r - separator when defined and in postfix position.

The terminator MTA region varies in size based on its starting alignment, and so it depends on the size of the shared region.

The postfix separator MTA region similarly varies in size based on where the tSkip region ended, and so it depends on the size of the shared region, and the sizes of the terminator MTA region, terminator, and tSkip regions.

|

|

The shared-after region does not have any sub-regions the size of which depend on the context. However, we separate it from the central shared region in order to separate all concerns around alignment and fill into separate regions from the central shared region, which could perhaps be called the shared content region. The central shared region therefore does not deal with alignment at all. |

The central idea here is that all the regions to the left (before) the known alignment point are context dependent. That is, whether these alignment fill and mandatory text alignment regions can be statically determined in size is dependent on where the prior term ended.

In contrast, the known alignment point is a fresh start for alignment. The alignment as required by the alignment properties will have been achieved at that point. Hence, from there and to the right (after), everything can be assessed relative to this new fresh anchor.

Inductively, even the context dependent regions are not dependent on terms very far back. Let’s consider the regions in a straddle of two adjacent terms in a sequence:

The Known Alignment Point 2 is only context dependent on the possible prior terms back to Known Alignment Point 1. This is true certaintly when Term 1 is a scalar element or a model-group itself.

In reality the induction here is more complex because Term 1 might be an optional element or an array, in which case the prior term before Term 1 may also be involved in computing the region sizes for the Term 2 unique-before regions. But this never needs to consider anything further back than the prior scalar term, or the start of the shared region of the enclosing model group, which need only be considered if Term 2 can be first within its enclosing model group.

|

|

Separators may be present even if terms are not, based on dfdl:separatorSuppressionPolicy and a few other properties. The diagrams show sequence before region as if it was part of the term, but really it may appear even if the term is absent. |

Given the above, for any term, we can compute its PropEnv, and create a distinct shared instance for that term for each unique PropEnv.

Since the shared region contains all the children of any child-containing term, sharing this insures that the schema compilation space/speed is proportional to, roughly, the size of the schema without any non-constant multiplicative factor. This insures no combinatorial explosion of compilation time.

A primary task of the schema compiler is to eliminate alignment fill (and mandatory text alignment aka MTA) regions that are unnecessary because the data can be proven to always be properly aligned.

This is done by computing, for each region, a compile-time alignment approximation. The AlignmentMultipleOf class represents this information. AlignmentMultipleOf objects form a mathematical lattice where perfect alignment is the bottom of the lattice, no alignment (or alignment multiple of 1 bit) is the top of the lattice, and various multiples (8, 32, etc.) live in between. For two lattice values a and b, we say a < b (a is 'weaker than' b) if a is a multiple of b.

A key observation is this: Each time we create an alignment constraint for a shared region, this is not dependent on any other constraint. That is, the constraints on alignment do not propagate from term to term. A shared region can assume it starts at the alignment that is required for the term based on the dfdl:alignment property, the initiator MTA if there is an initiator, and the value MTA for text-representation simple values.

Hence, terms that appear down-stream of any shared region do not depend on any constraints propagating from before the shared region. This greatly reduces the complexity and the distance across the schema that constraint-changes propagate. It also insures there is no need for an iterative contraint solver, since nothing about alignment propagates from one term to the next. Terms are separated by the fact that the shared region of a term starts from a known alignment (specified by its alignment and alignment units property).

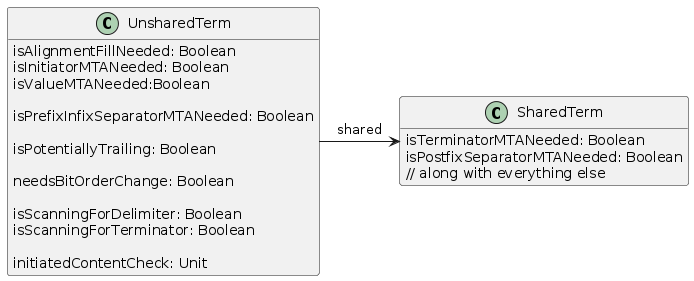

By dividing up the representation of a term into the unique context-dependent and shared context-indepenent parts explicitly we provide a home for the various calculations the schema compiler performs in order to do other optimizations.

In the above class diagram, members that must be computed on the unshared term object are shown in the class. This set of things should always be minimized. That is, as few things should be computed on unshared term objects as posible. It is assumed that everything else is computed on the shared term object, but members specifically about regions discussed in sections above are called out.

The UnsharedTerm object is effectively state of the enclosing model group DSOM object. It exists in 1 to 1 correspondence (aka it is "owned" by the enclosing model group object.)

In the Runtime 1 backend, a processor (parser/unparser) is generated for the shared term object, and that processor is referenced from the processor generated for the unshared term object.